Longitudinal effects of independent walking on postural and object experiences in home life

John M. Franchak1, Kellan Kadooka1, & Caitlin M. Fausey2

1University of California, Riverside

2University of Oregon

Walking augments exploration

Walking independently lets infants:

Take more steps and spend more time in motion (Adolph et al., 2012)

See distant objects and locations (Kretch et al., 2014)

More easily carry objects (Karasik et al., 2011, 2012)

- These benefits suggest that walking ability facilitates developmental cascades (Oudgenoeg-Paz et al., 2016; Walle & Campos, 2014)

Motor devel. ➝ object exploration

Sitting > Supine/Prone (Soska & Adolph, 2014)

Motor devel. ➝ object exploration

Crawlers > Walkers (Herzberg et al., 2021)

Characterizing opportunities for learning

- Skills only matter if they’re used…

Brief lab or home visits miss the potential moderating effect of daily routines (e.g., playing, feeding)

Video observation may bias infant and caregiver behaviors (Bergelson et al., 2019; Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2017)

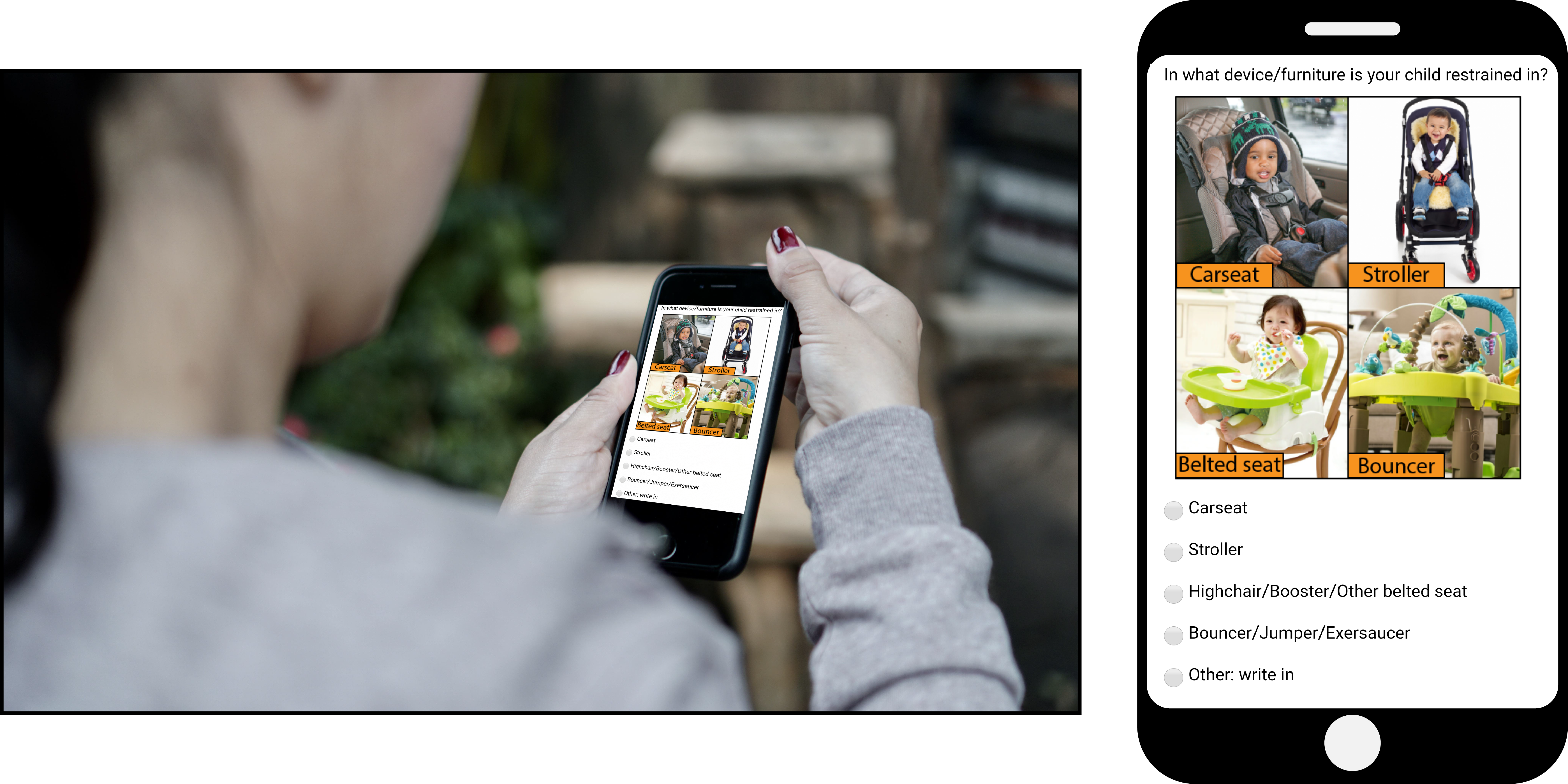

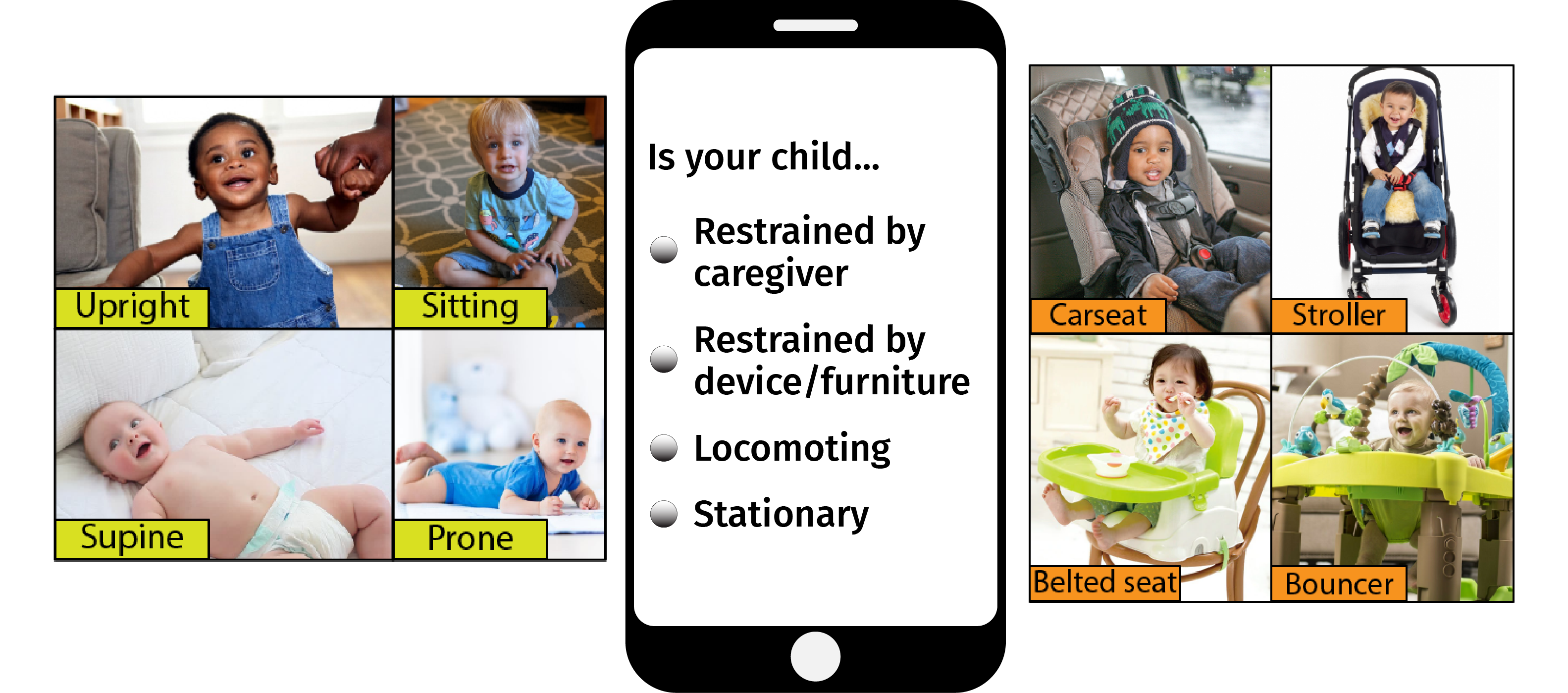

Ecological Momentary Assessment

Prompt caregivers to observe infant behavior in brief phone surveys multiple times per day (Franchak, 2019)

Aims of current study

Longitudinal EMA sampling from 10-13 months to:

Assess how the emergence of walking alters time spent in different body positions and time spent restrained by furniture/caregivers

Determine how everyday object holding changes based on infants’ body position and restraint

Capturing full-day experiences

Capturing full-day experiences

Participants

- Scheduled sessions at 10, 11, 12, and 13 months (± 1 week)

- N = 62 participants (34 female) contributed M = 3.6 sessions, responding to M = 28.3 samples/session

| Session | # Infants | Min | Mean | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 52 | 9.71 | 9.98 | 10.31 |

| 11 | 57 | 10.76 | 11.01 | 11.34 |

| 12 | 58 | 11.78 | 12.00 | 12.32 |

| 13 | 54 | 12.70 | 13.00 | 13.34 |

Participants

Families recruited from 29 US states

| Ethnicity | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Hispanic or Latino | 11 | 17.7 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 51 | 82.3 |

| Race | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Asian | 1 | 1.6 |

| Black Or African American | 1 | 1.6 |

| More Than One Race | 7 | 11.3 |

| Other | 7 | 11.3 |

| White | 46 | 74.2 |

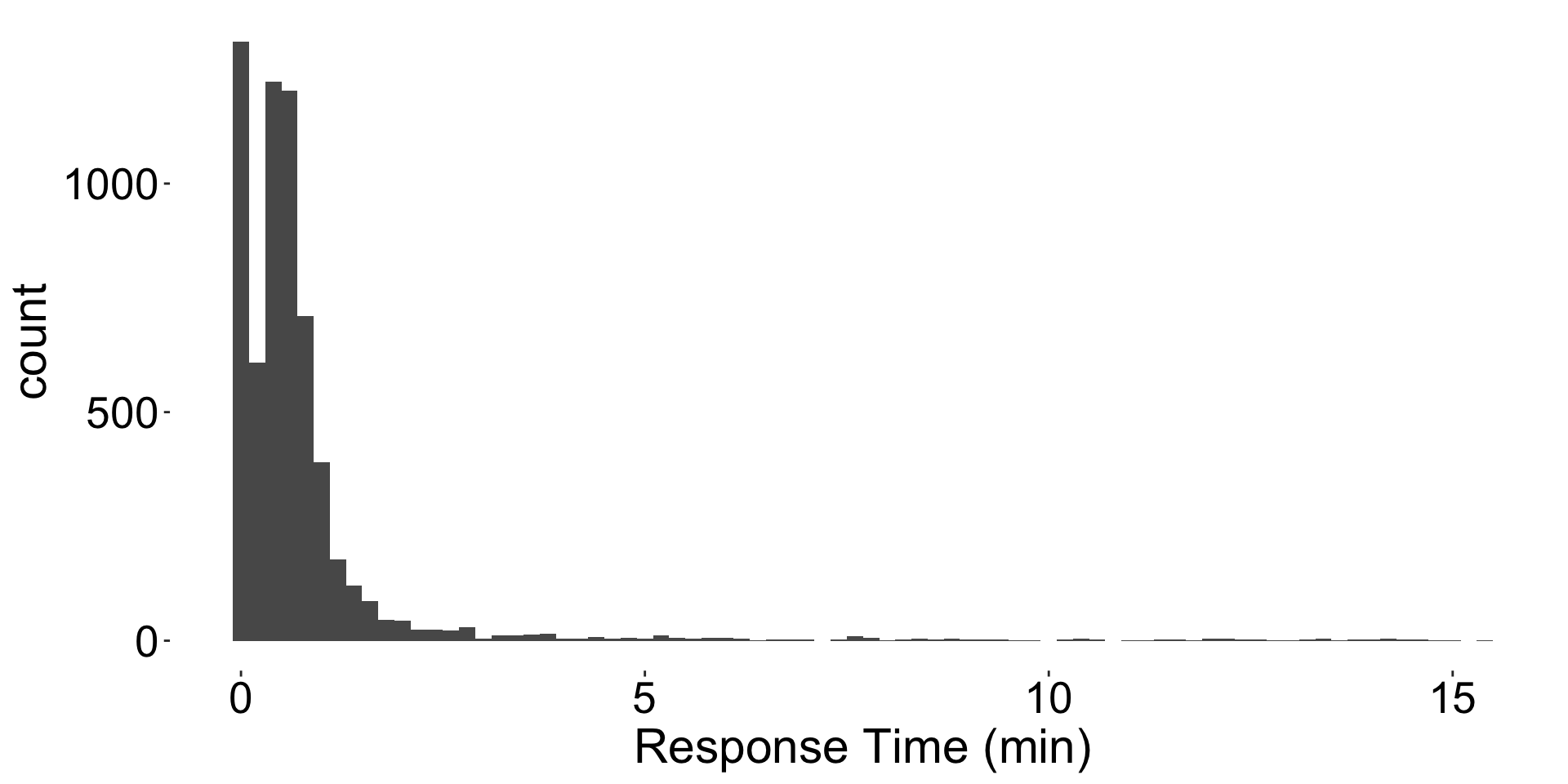

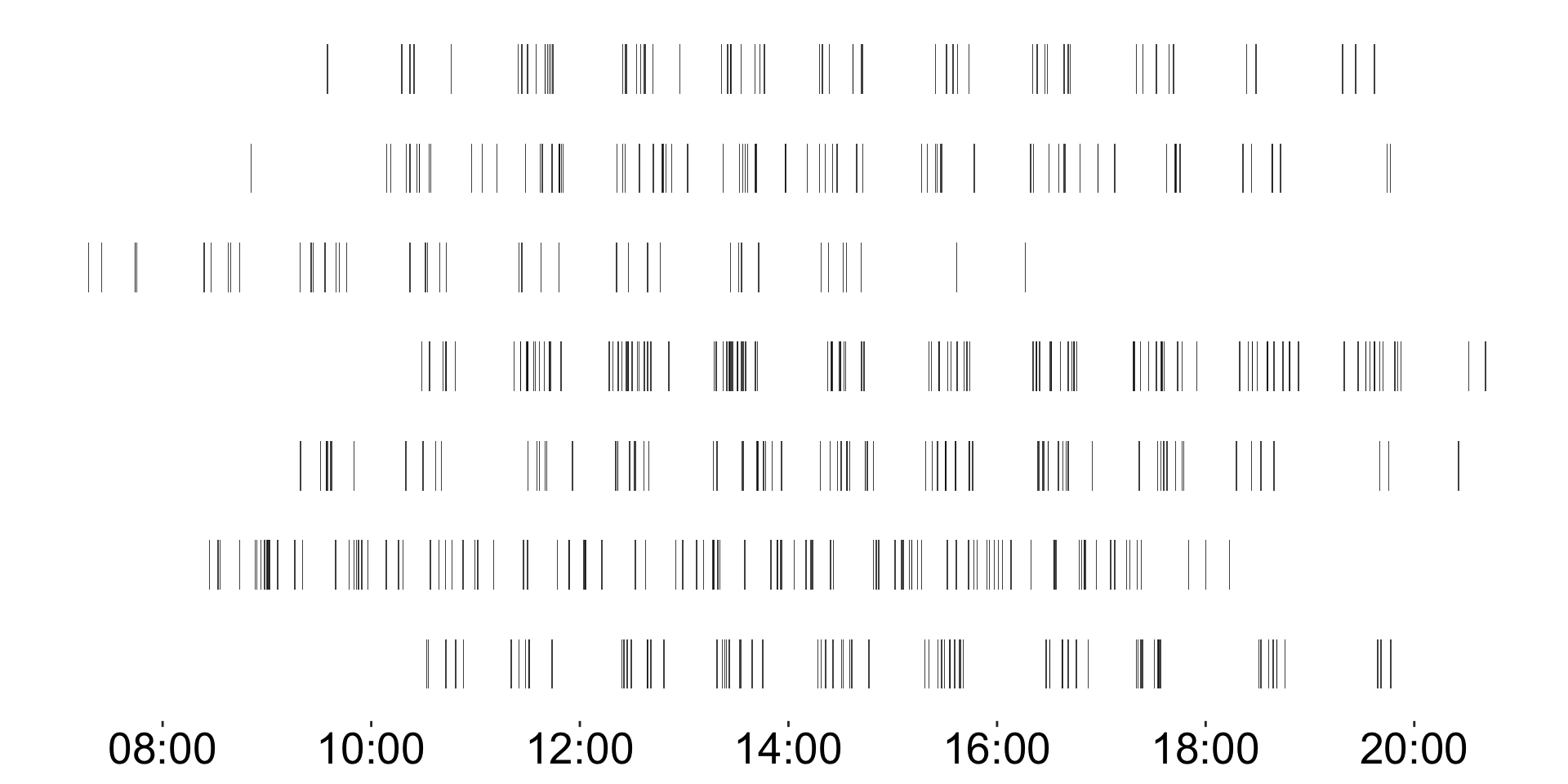

Samples reflected in-the-moment behavior

Response time = time between text and completing the survey

Responses had to be made within 15 minutes

Response time median = 0.5 minutes

84.2% of texts were responded to within 1 minute

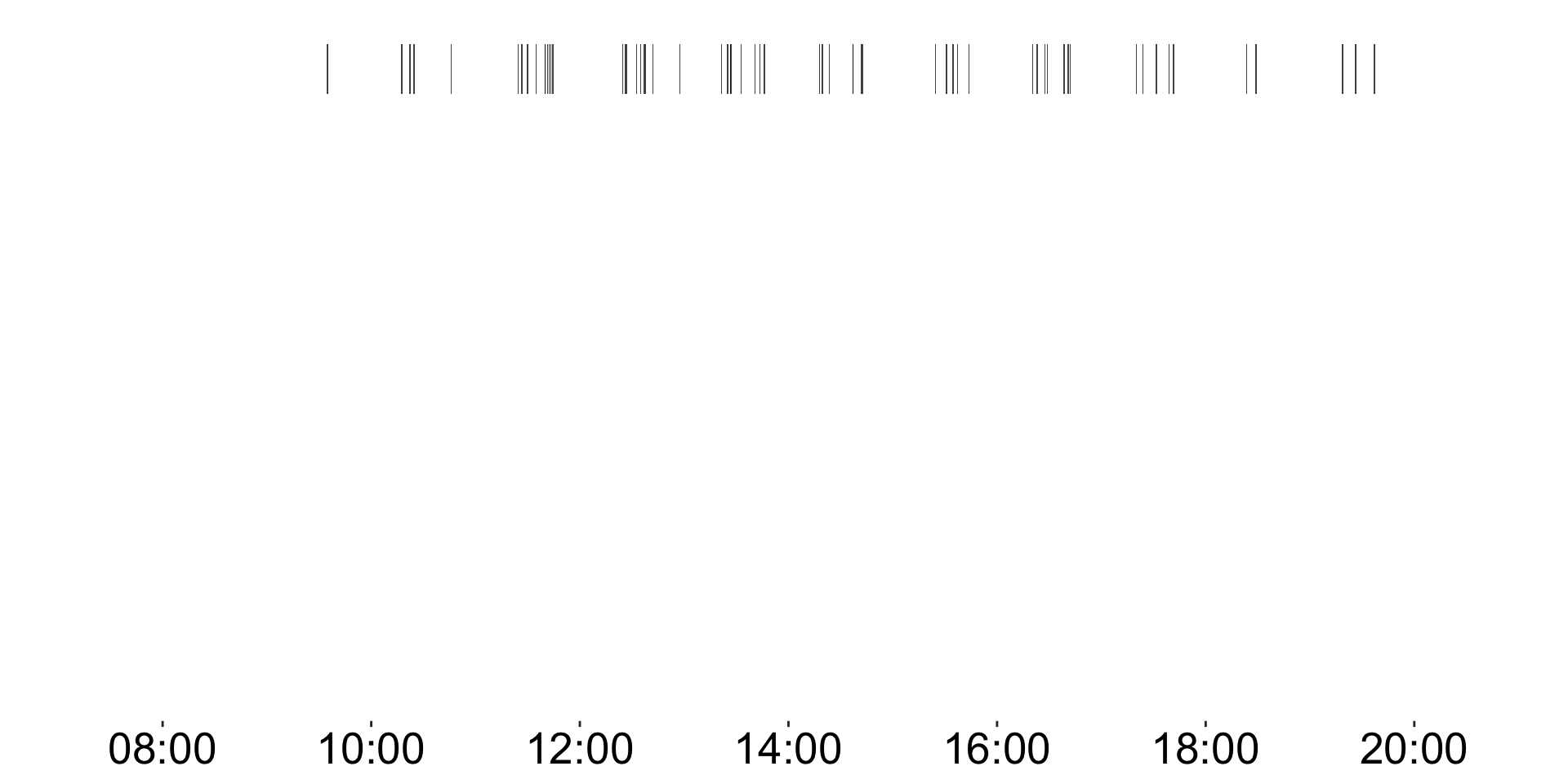

Samples were distributed across the waking day

Samples were distributed across the waking day

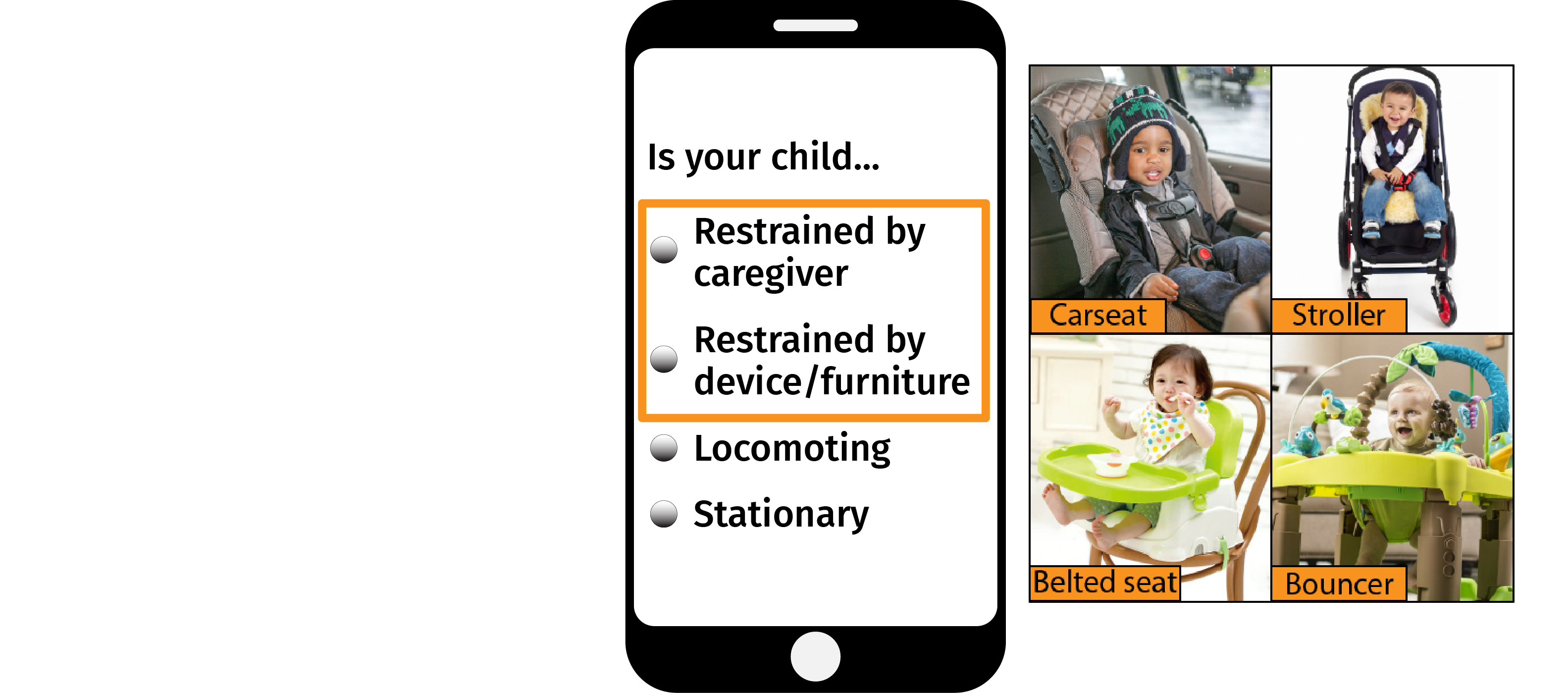

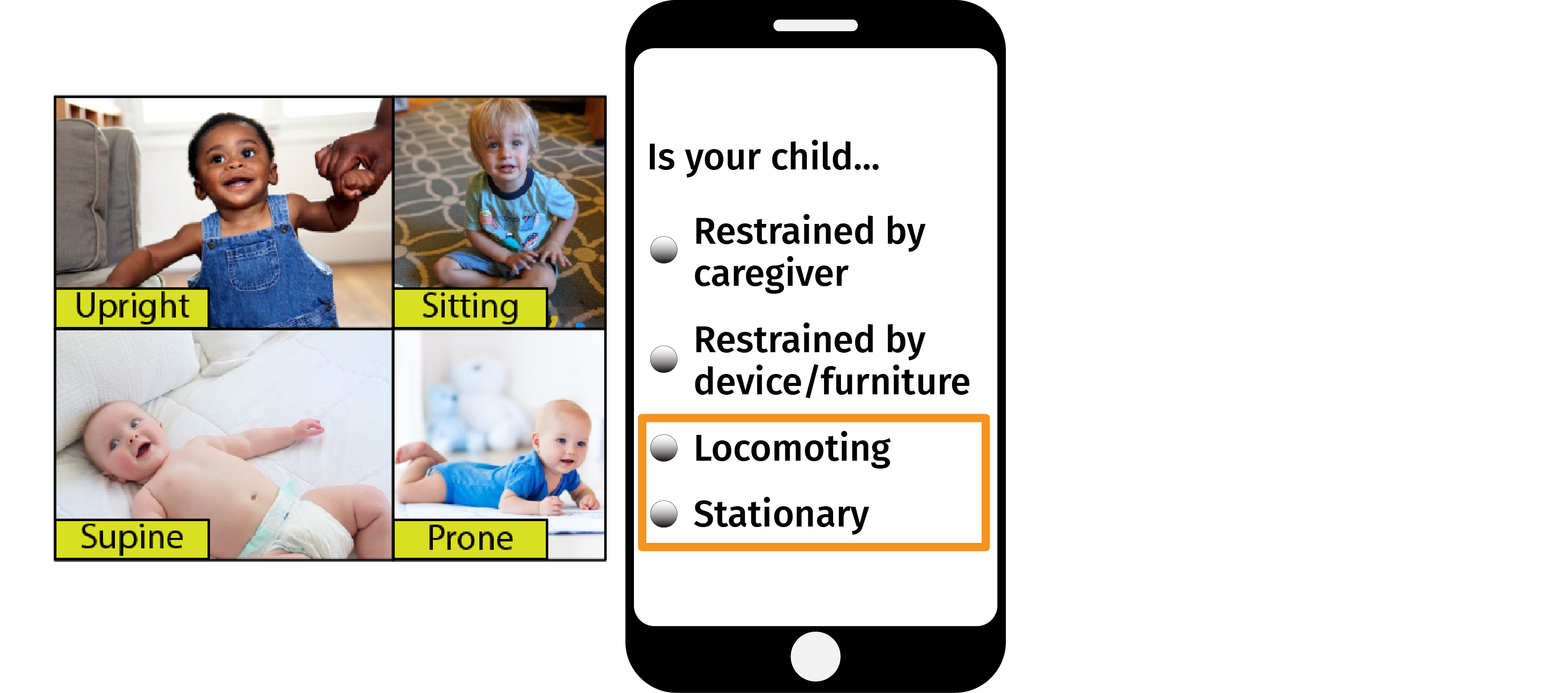

Measuring body position and restraint

Measuring body position and restraint

Measuring body position and restraint

Measuring body position and restraint

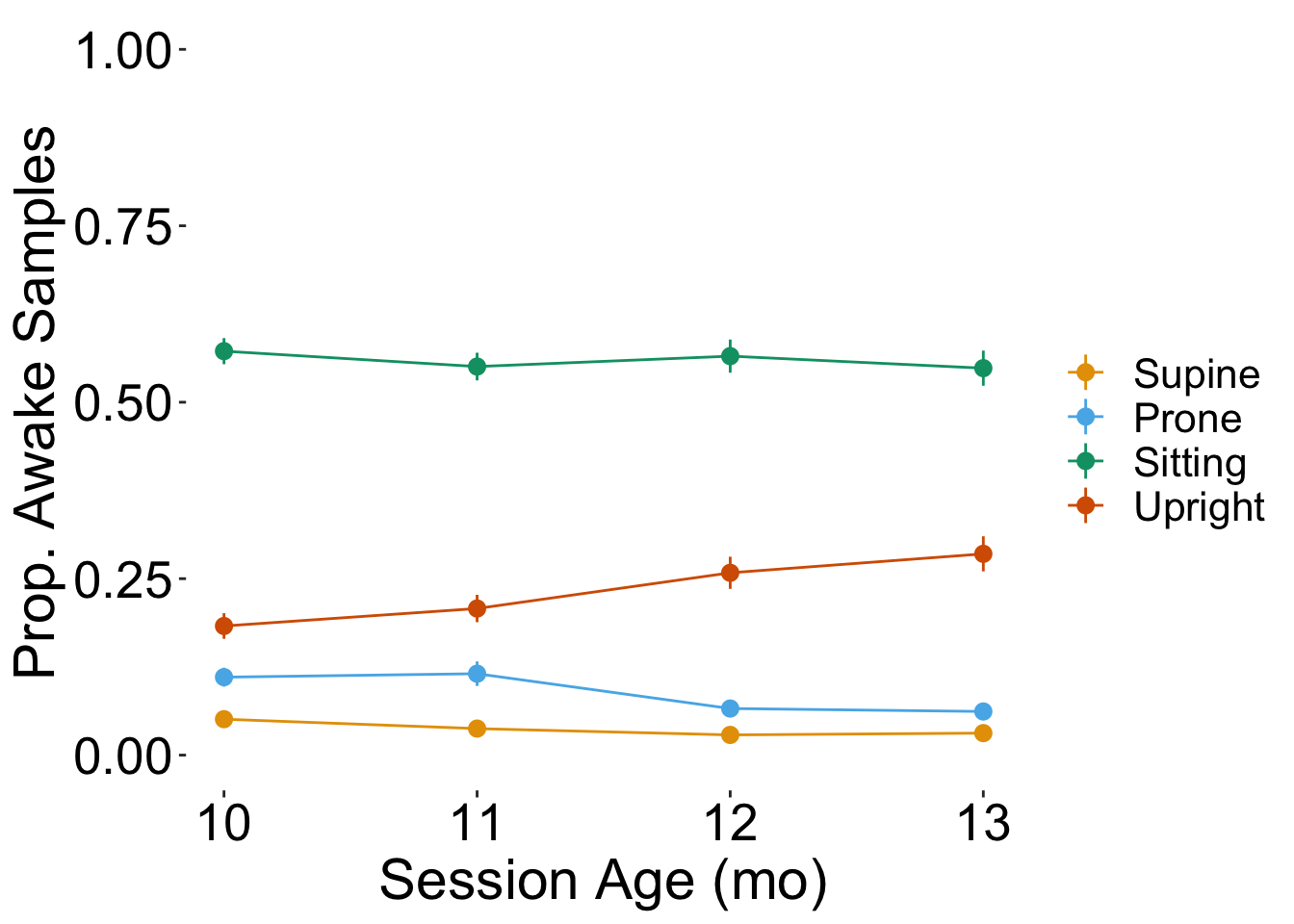

With age, prone decreased and upright increased

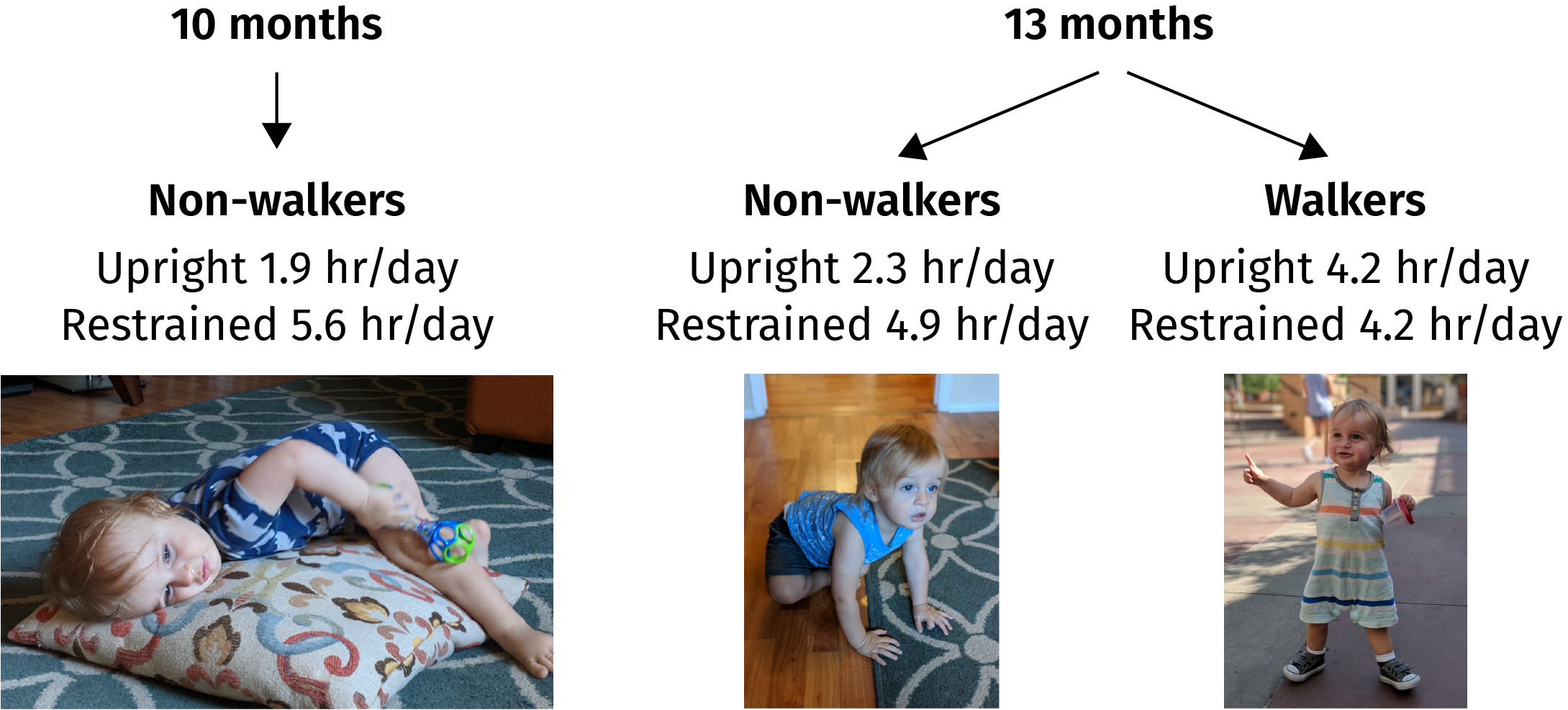

How did walking alter daily experiences?

After each session, a structured phone interview determined whether the infant had begun walking

Infants were considered walkers if > 25% of their samples in a session occurred on or after their walking onset date

| Session | Walking | Not Walking |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | 3 | 49 |

| 11 | 8 | 49 |

| 12 | 17 | 41 |

| 13 | 25 | 29 |

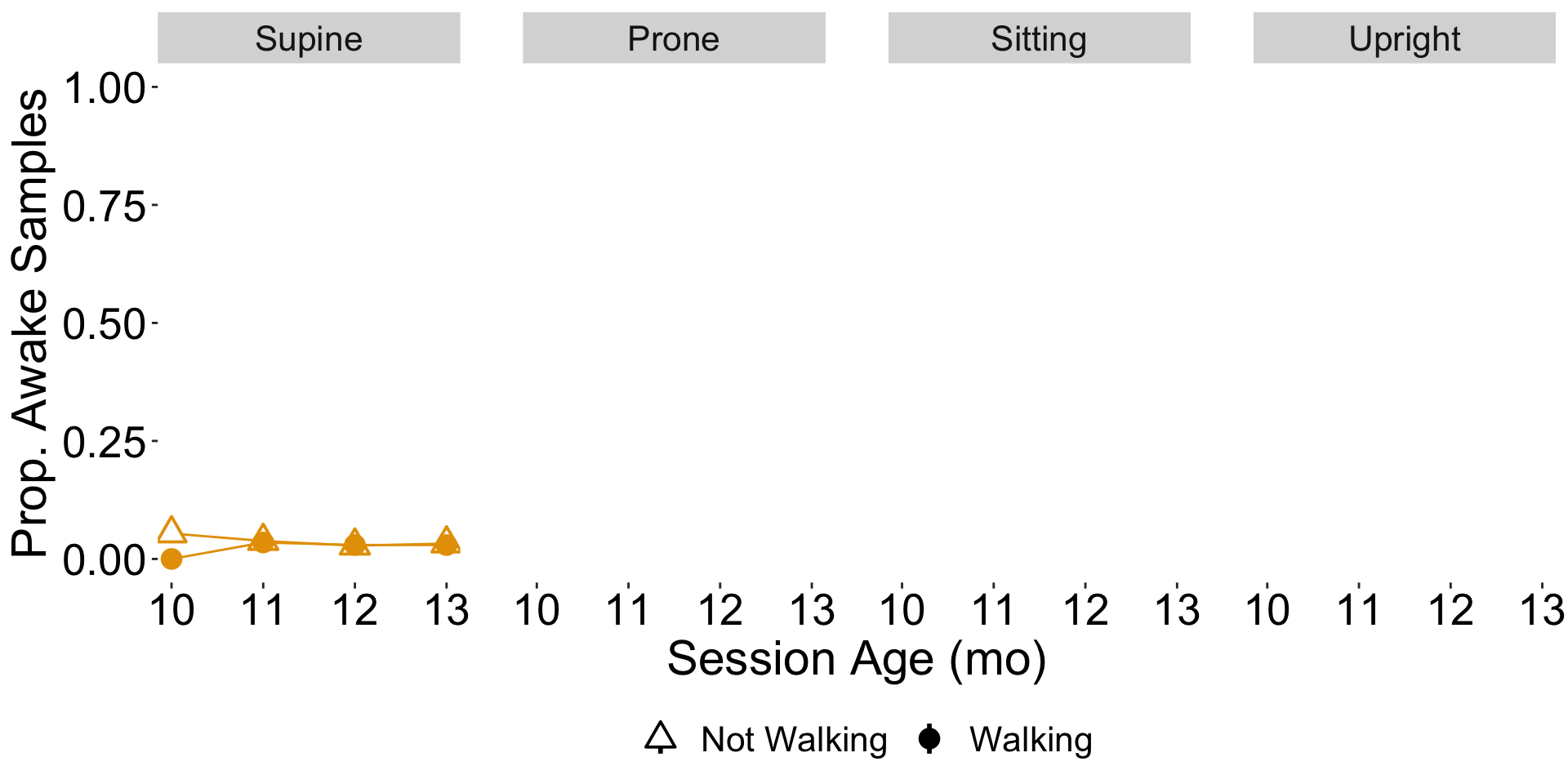

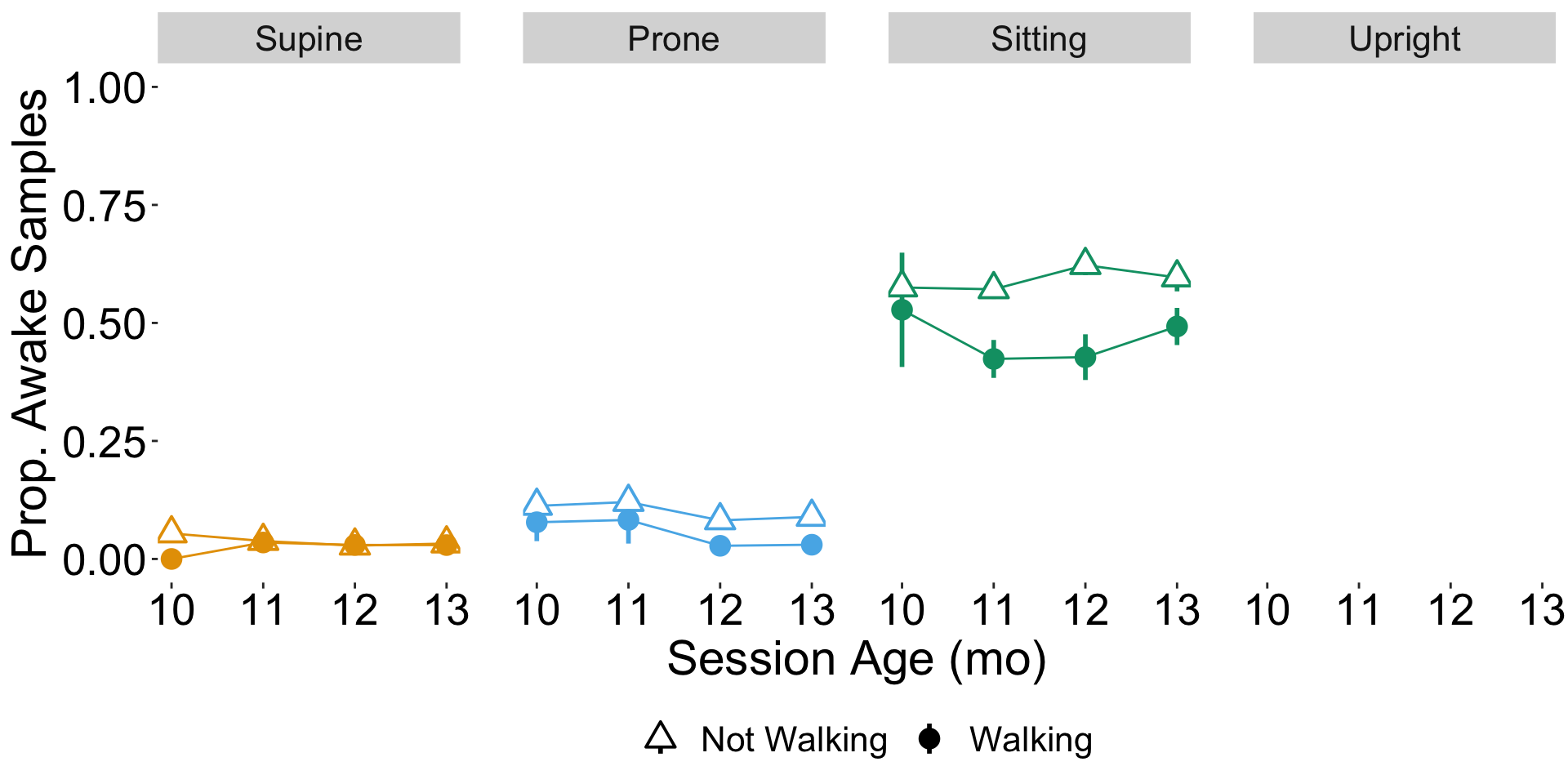

No difference in supine by age or by walking

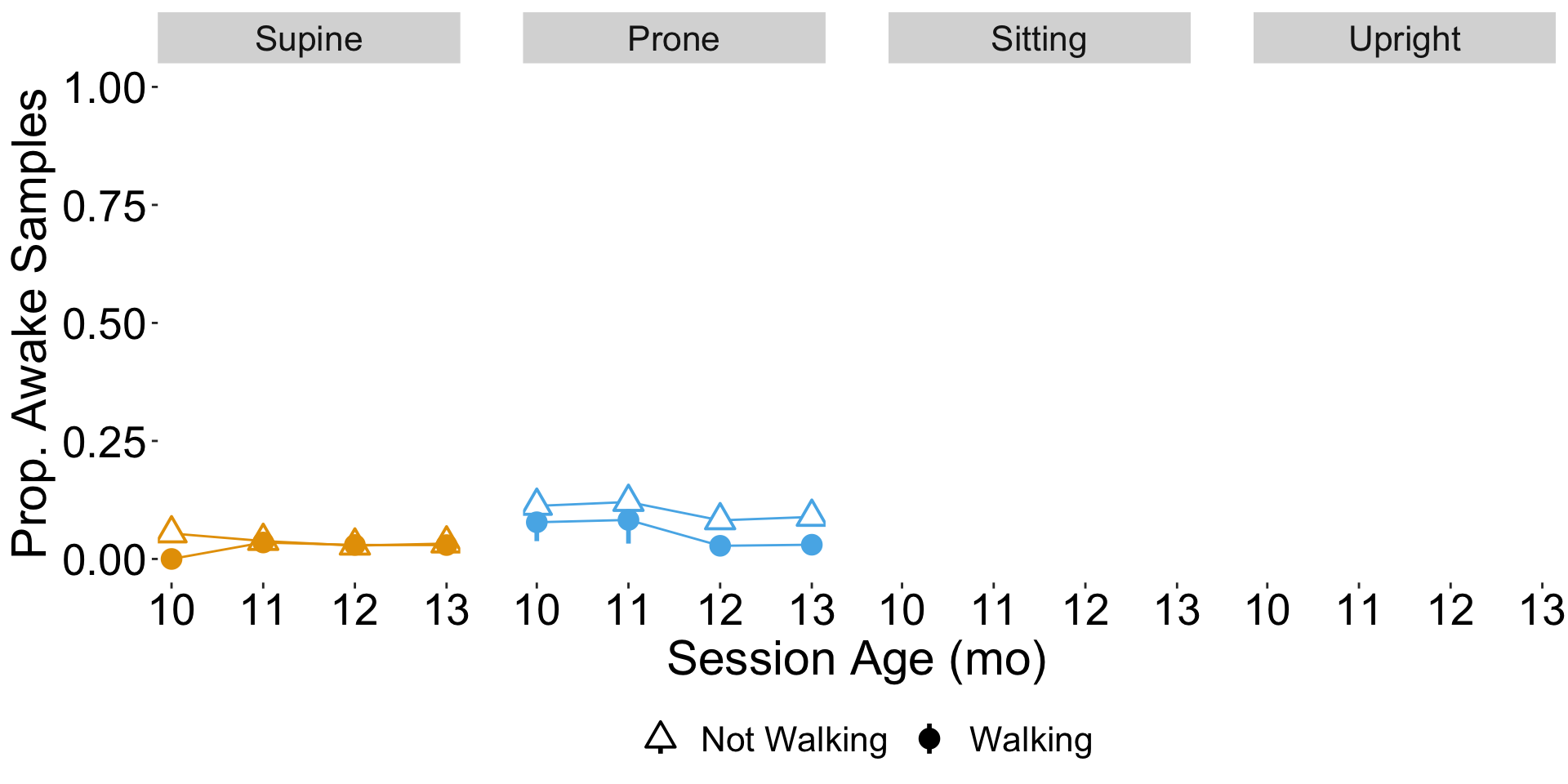

Prone time decreased by age and walking status

Non-walkers sat more than walkers regardless of age

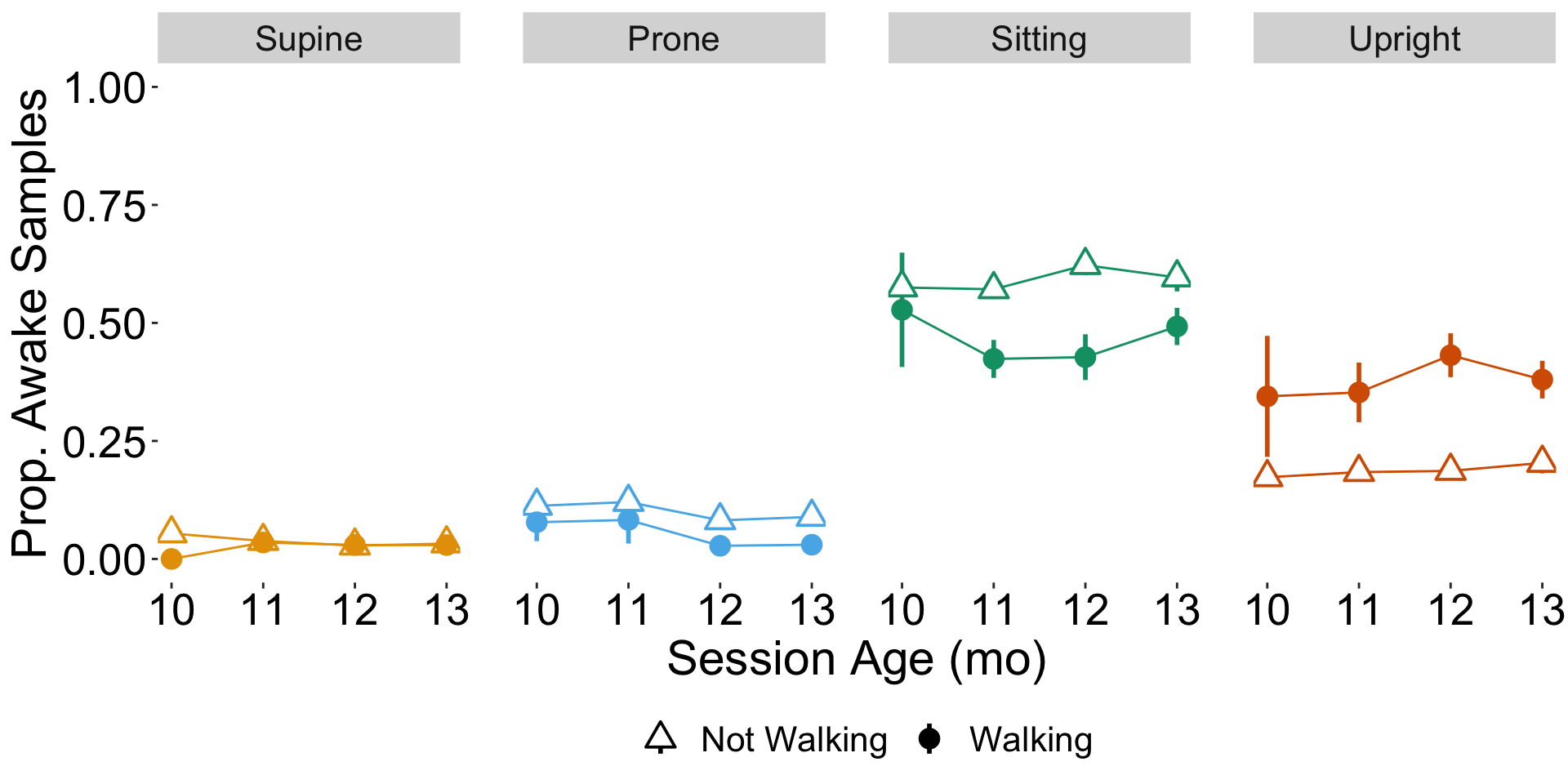

Upright time increased with age and with walking status

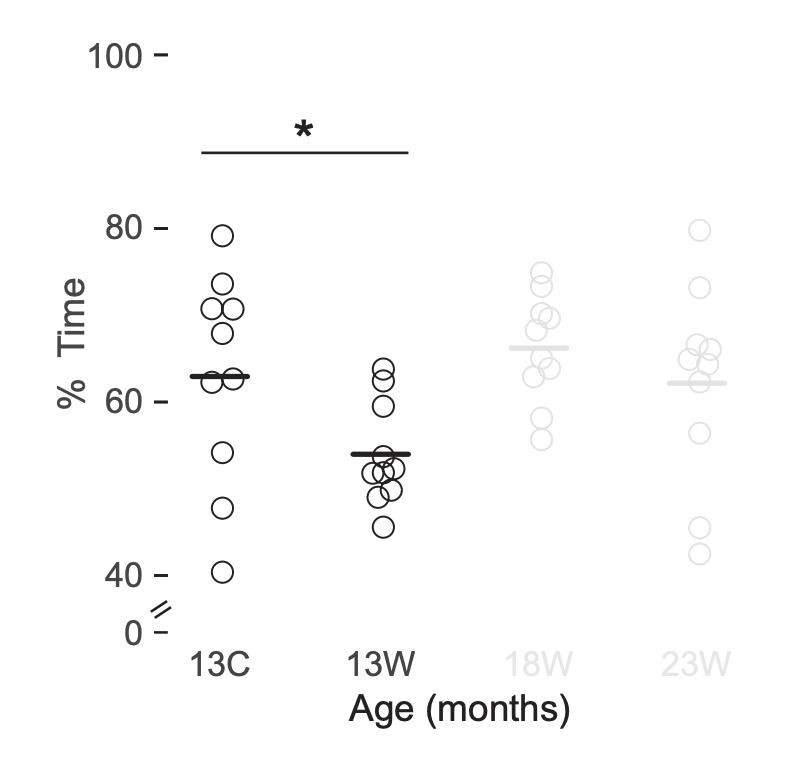

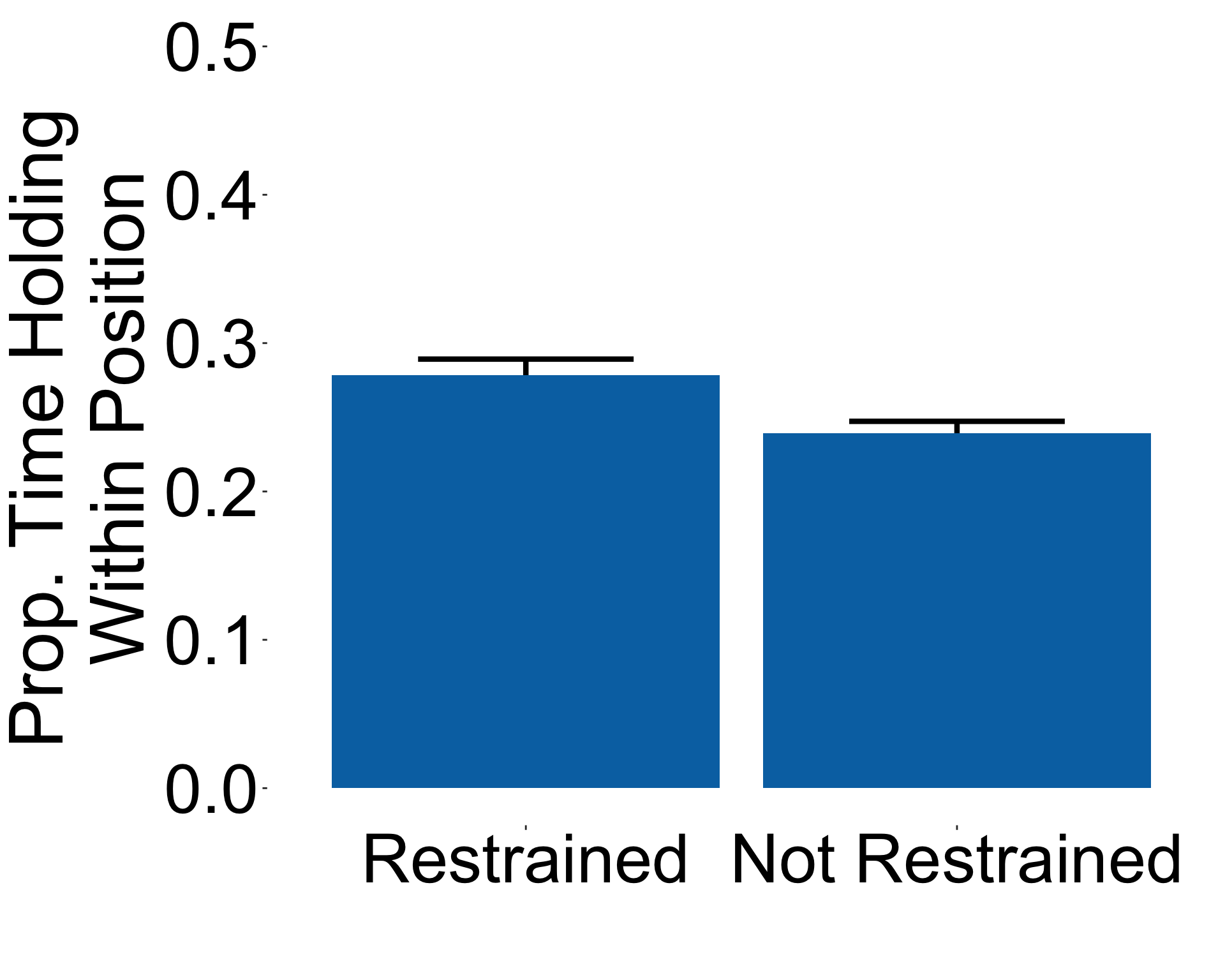

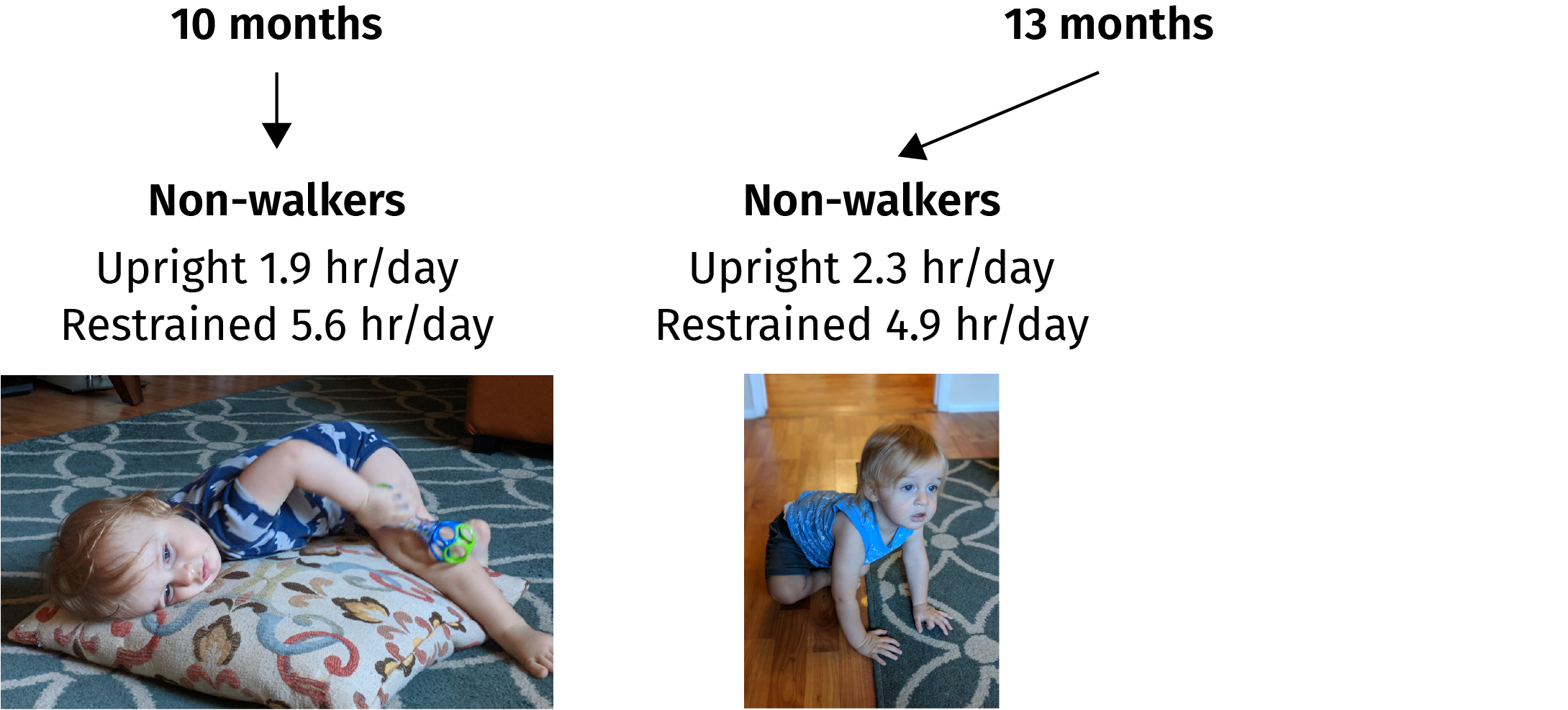

Restraint decreased with age/walking

Restraint time decreased from 49.6% at 10 months to 41.1% at 13 months

Non-walkers were restrained more frequently (M = 48.2%) than walkers (M = 38.9%)

Daily object holding experiences

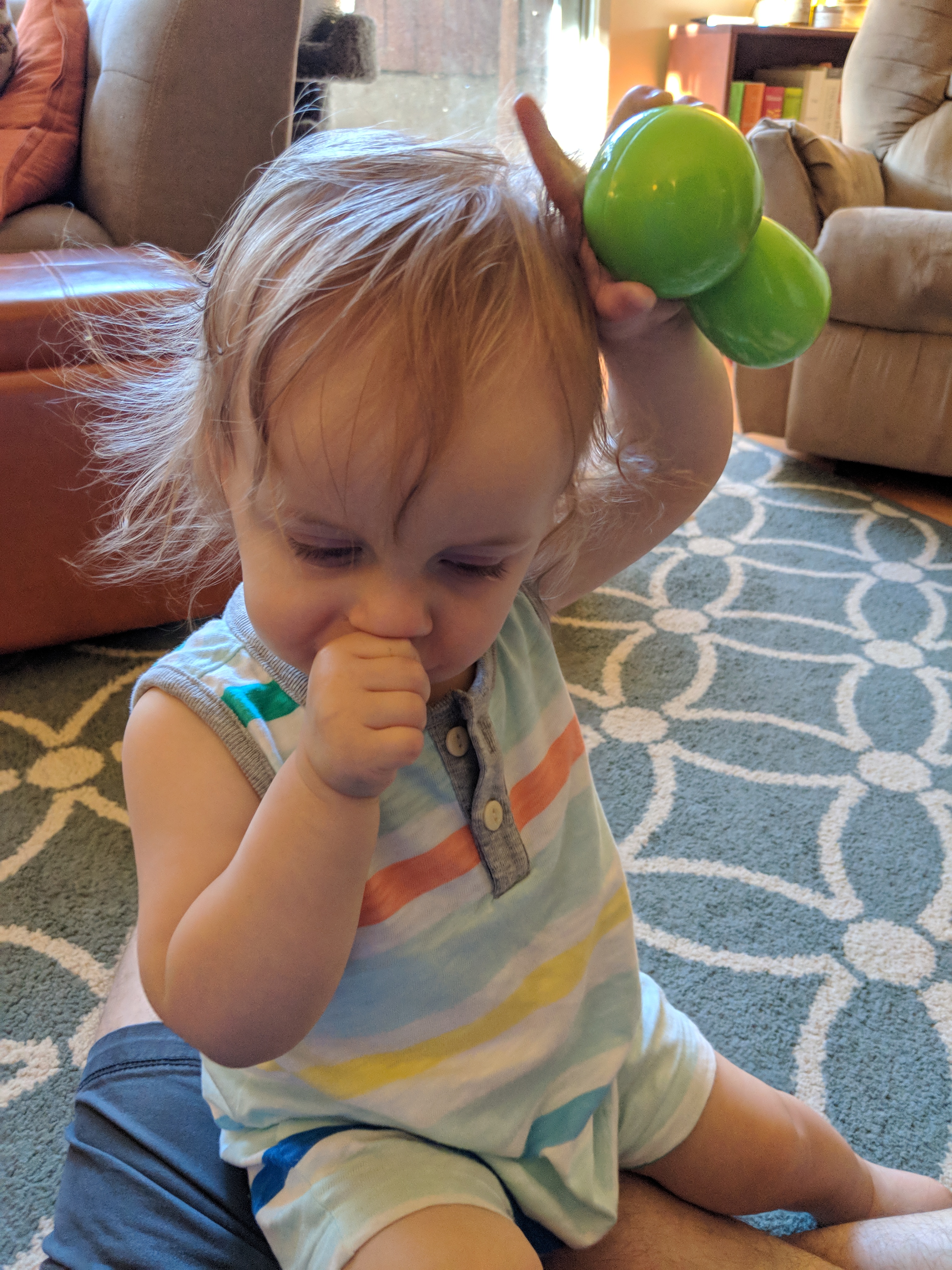

Infants held objects 40.4% of the time—roughly 4.5 hours each day, based on an 11.1-hour waking day (Galland et al., 2012)

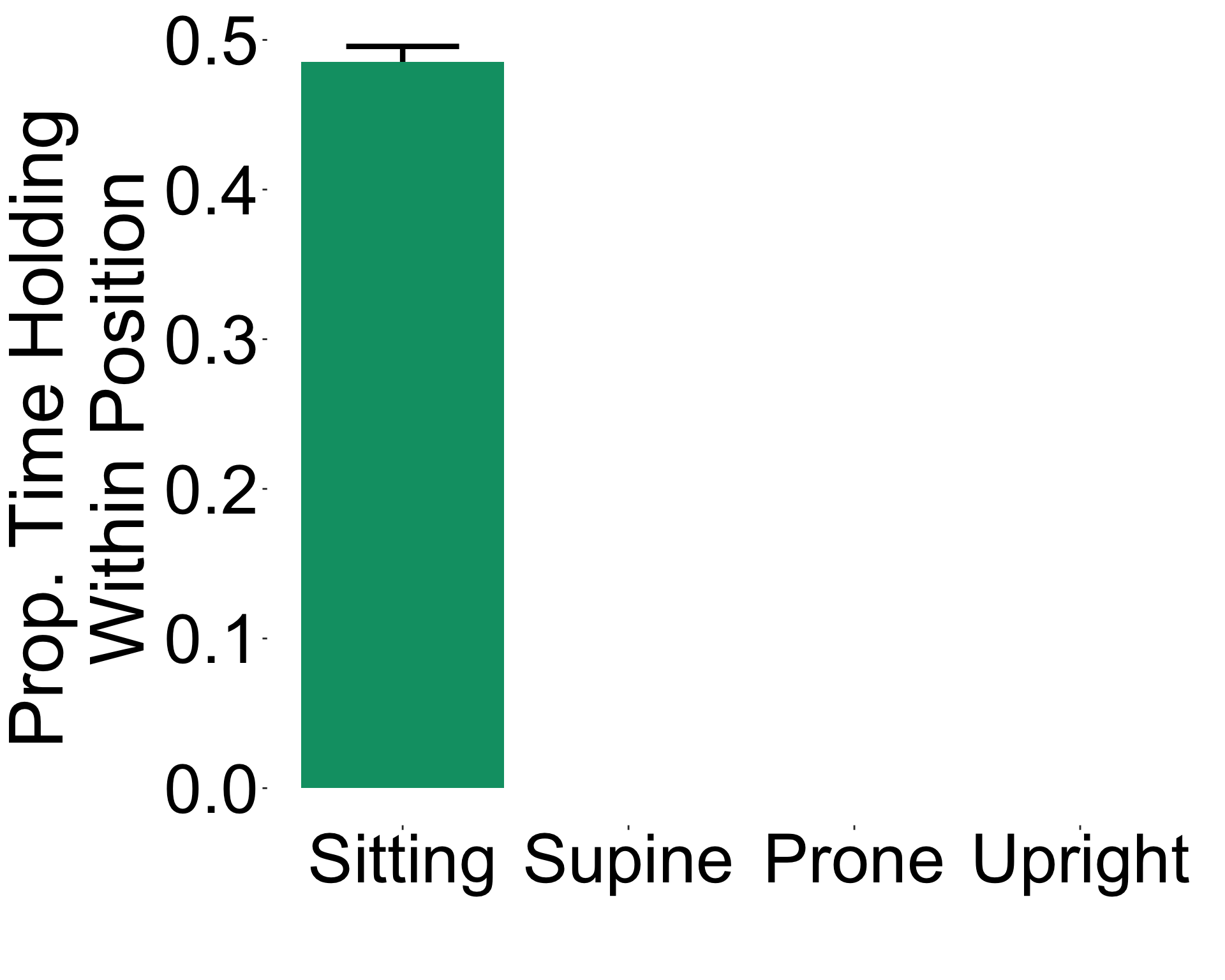

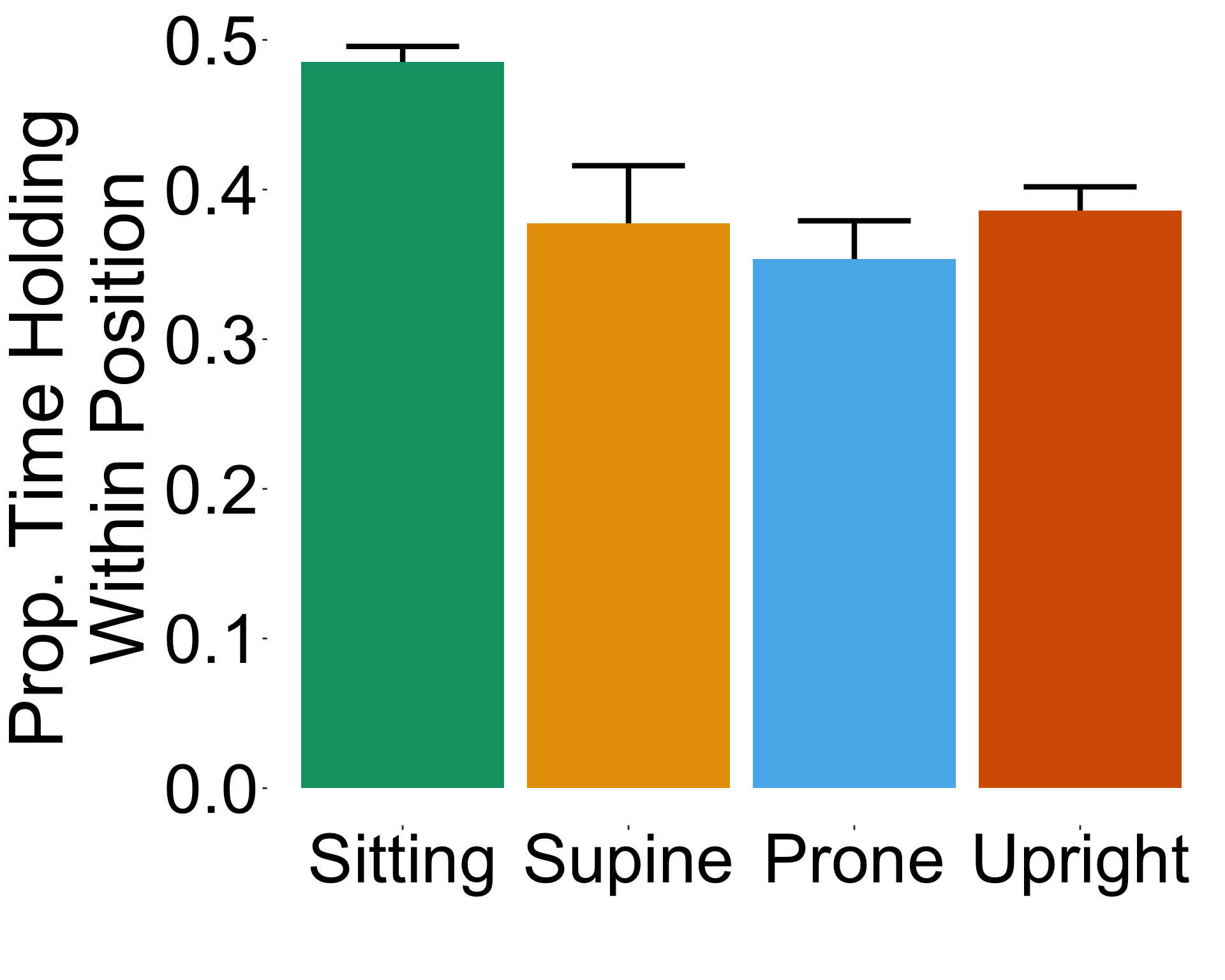

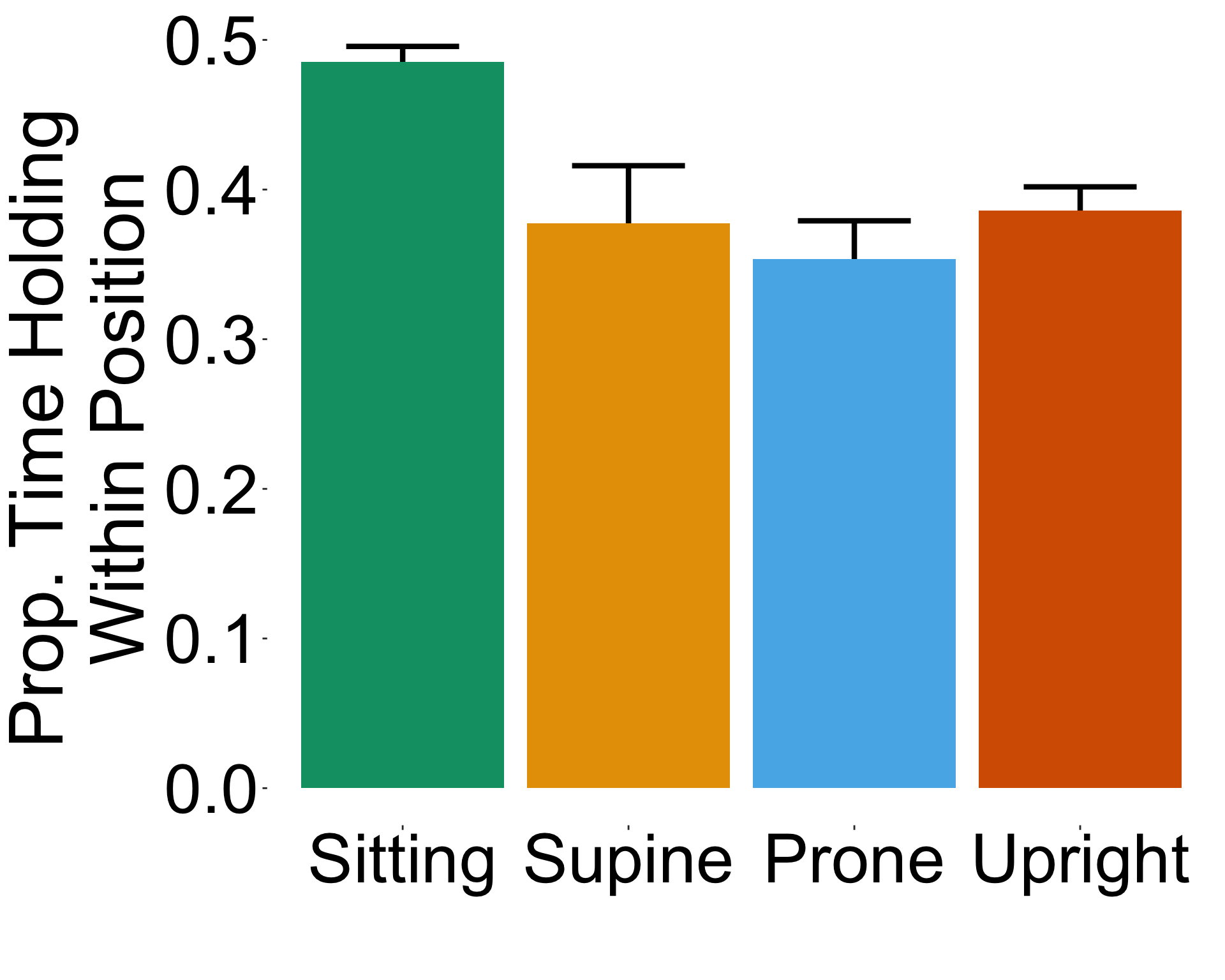

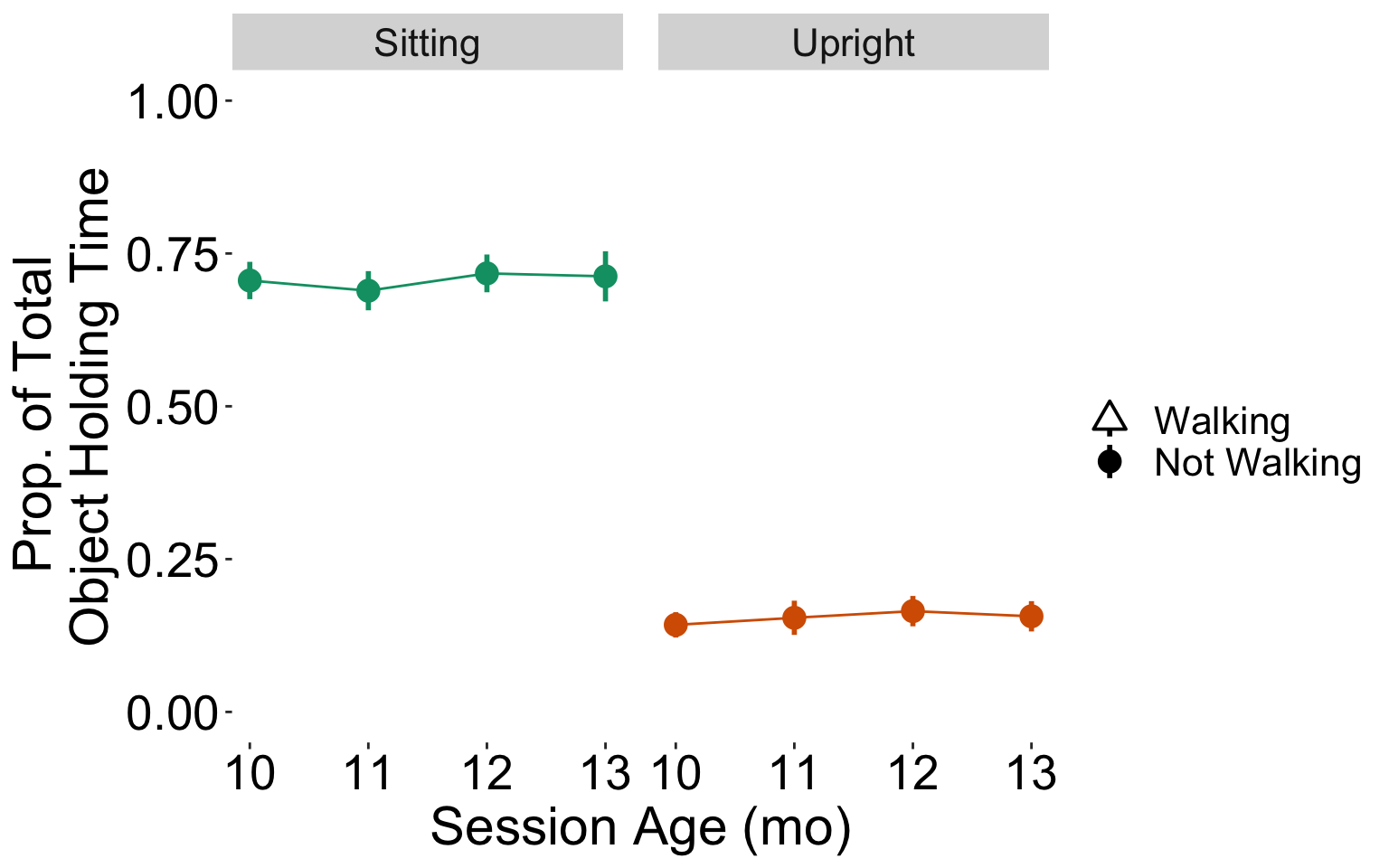

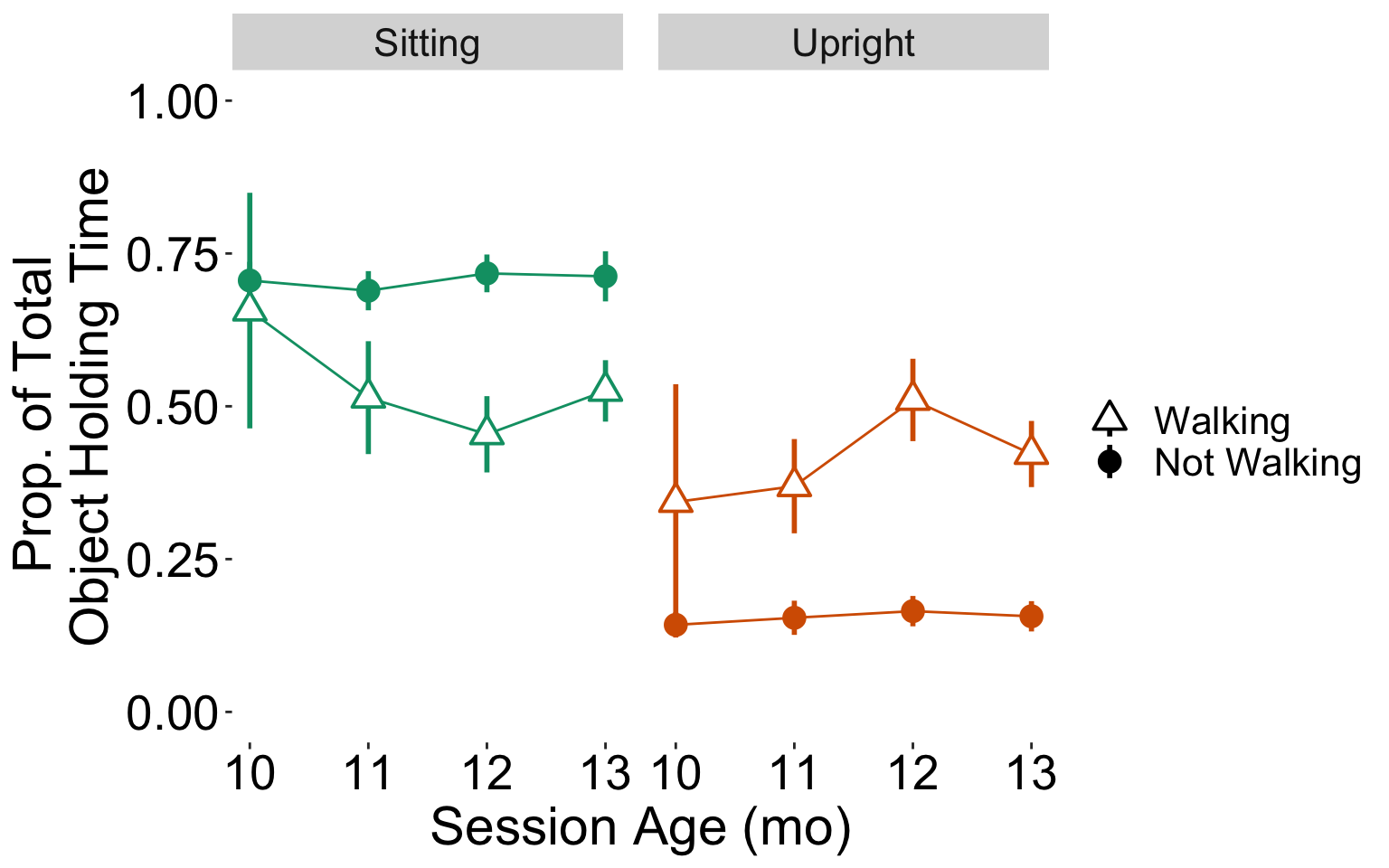

What proportion of sitting time did infants spend holding objects?

Body position and restraint moderate object experiences in the moment

Body position and restraint moderate object experiences in the moment

Two possible effects

- Overall change in holding: Walk onset ➝ decreased time sitting ➝ decreased overall-object-holding-time

- Holding adapts to motor context: Walk onset ➝ decreased time sitting ➝ upright-object-holding-time increases while sitting-object-holding-time decreases

Walking infants integrate object holding into new time spent upright

Walking infants integrate object holding into new time spent upright

Summary: What experiences change over development?

Summary: What experiences change over development?

Summary: What experiences change over development?

Non-walkers hold…

3.2 hrs/day while sitting

0.7 hrs/day while upright

Walkers hold…

2.1 hrs/day while sitting

1.8 hrs/day while upright

Conclusions

- Effects at multiple timescales

Conclusions

Effects at multiple timescales

Dissociable effects of age and walking ability

Conclusions

Effects at multiple timescales

Dissociable effects of age and walking ability

Multiple drivers of change

Acknowledgments

Data Collection Team

Chase Butler

Madelyn Caufield

Ariana Diaz

Juelle Ford

Tasnia Haider

Sasha Kapadia

Preet Kaur

Vanessa Scott

Funding

NSF BCS-1941449

UCR Regents Faculty Award